Sometimes I look East, Sometimes I look West. Bouke De Vries

The practice of London-based Dutch-born artist Bouke de Vries perfectly reflects our time, feeding on the contemporary paradox of beauty: a spasmodic research of uniqueness and perfection wrapped in the aesthetic banalization of consumerism. His artistic vision stems from his own experience as a ceramics conservator. De Vries refutes the underlying western attitude that once something is broken it is only fit to be discarded. Even those who take care of preserving works of art often choose to disguise as much as possible the memory of the suffered trauma. Instead he considers himself closer to the Chinese and Japanese tradition of repairing important objects so that the breakage is celebrated, rather than hidden.

A game of opposites that chase each other, as in the new Milanese exhibition by the artist titled "Sometimes I look east, sometimes I look west". Quiet, thoughtful but at the same time witty and subversive, de Vries’s sculptures offer a second narrative opportunity to exquisite objects, such as a Cocoon Jar from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), which changed its essence in a few moments from fetish to potsherd. De Vries skillfully deconstructs these ancient fragments, giving them a new symbolism. The swarm of butterflies surrounding the pot in "Resurrection Jar" alludes on the one hand to the cocoon shape of the vase, and on the other to their iconographic use as a symbol of the resurrection in the famous still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age.

China and Holland are the extreme poles of his narration. The first seen as the driving force of ceramics manufacture throughout history, the second, as well as his home country, a nation that reaches world power in 17th century, via their trade with the east. Ceramics played a pivotal role in this, not only porcelain from China but also Dutch Delftware, much of it inspired by Chinese porcelain. However, de Vries's interest is not limited to a reflection on the genesis of ceramic products, their forms, their uses and symbols. His intellectual curiosity embraces historical and sociological insights into the context in which – yesterday as today – these are realized or exchanged.

Following this perspective, the rebirth of China as a global superpower becomes one of the most fascinating and urgent themes. De Vries reminds us of Napoleon Bonaparte's warning: “China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep, for when she wakes she will move the world.” The artist's work constantly reiterates the lesson of the Dutch masters de Heem, Kalf, van Alst and van Huysum, in whose paintings common pottery – milk jug, teapot or cress drainer – is imbued with references to vanitas and memento mori. Fruits, flowers and the small insects that accompany them were, in fact, indicators of veiled ethical and spiritual references.

In his oeuvre aesthetic conundrums find unexpected possible interpretations. In "Two Tang Soldiers" one of the pair of Tang dynasty (618-907) terracotta soldiers presents the typical earthy color and appearance of an archaeological find, while the other is painted by the artist with bright primary colors. Although the modern viewer is used to look at ancient objects – like, most famously, Greek marbles – in all their monochrome beauty, pure and white, in fact these pieces were originally painted, often in colours now considered garish. The same is true with the muddy nuances of these terracotta artifacts from China. Pairing these two soldiers reflects on today's aesthetic perception of these works in relation to the moment of their creation. De Vries does not take a position, but contrasts how the history of taste proceeds in an uninterrupted dialogue with the history of art; an apparently kitsch aesthetic can reveal a profound hidden truth.

Artworks by de Vries may be exploded, combusted, destructured or, on the contrary, recomposed using the kintsugi technique – the Japanese practice of using gold to reconnect the fragments of ceramic objects – the quality of execution is what distinguishes each of these technics. "There was a time,” says de Vries, “when quality was not considered an integral part of a contemporary work of art: the idea was the essential parameter for its success. But now I think there is a return to a vision of the artist as a producer, as someone who possesses a particular creative ability that allows him to give life to sublime works.” This does not mean rejecting the lessons of the contemporary that in his work is exalted through countless Dadaist, Surrealist and Pop quotes. In an aesthetic remix in which inspirations drawn from the world of high culture clash with those of low culture, we move from the Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti ("Egypt" 2013) to The Simpsons ("Marge Simpson as Guan Yin Goddess of Compassion" 2014).

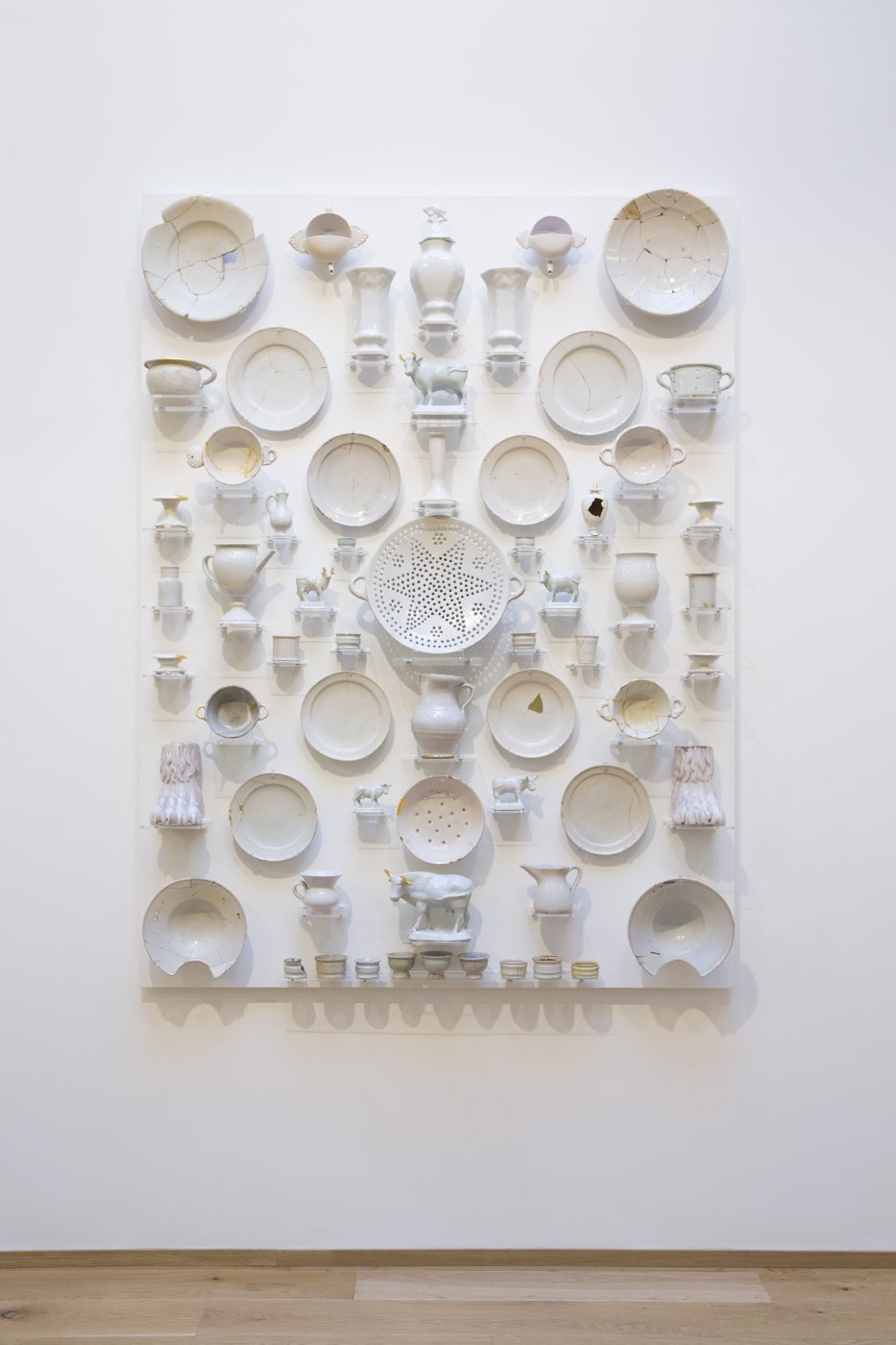

Each sculpture by de Vries, while maintaining a dialogue with all his other works, remains essentially a single piece. This is one reason why the artist does not make use of assistants but creates every single work by himself. His sculpture is much about composition, balance and aesthetic. A lot of it develops in fieri as he works on it. In this context the largest work on show, "The Wall 2," is especially relevant. An installation of white Delftware inspired by the French-born, Dutch architect Daniel Marot, whose elaborate interior designs helped define the decorative style of Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. Marot’s wall schemes of blue and white Chinese porcelain were a status symbol of the time. In 2012 de Vries was invited to create a monumental work inspired by Marot by the English museum, Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, who commissioned him to create a site-specific installation for the museum's grand staircase. The temporary installation "Bow Selector" comprised four consecutive panels presenting in a unique and innovative way the museum’s precious collection of almost three hundred pieces of Bow Porcelain (London, 1747 to 1764). By contrast, for "The Wall 2" de Vries deliberately chooses only fragments of Delftware, saved from centuries old rubbish tips and dredged from the bottom of canals. These objects were not celebratory but kept for everyday use: it’s the artist who now gives them a new cultural status.

In this and other works on show the archaeological remains are the starting point for a new narrative. Perhaps one day they too will disappear into the earth and perhaps will be found in an unimaginable future. What stories will they tell then?

Born in 1960 in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Bouke de Vries studied at the Design Academy Eindhoven, and Central St Martin’s, London. After working with John Galliano, Stephen Jones and Zandra Rhodes, he switched careers and studied ceramics conservation and restoration at West Dean College. Every day in his practice as a private conservator he was faced with issues and contradictions around perfection and worth.Using his skills as a restorer (c.f. Ron Mueck’s model-maker skills), his ‘exploded’ artworks reclaim broken pots after their accidental trauma. He has called it ‘the beauty of destruction’. The more contemplative works echo the 17th- and 18th-century still-life paintings of his Dutch heritage, especially the flower paintings of the Golden Age, a tradition in which his hometown of Utretch was steeped (de Heem, van Alst, van Huysum inter alia), with their implied decay. By incorporating contemporary items a new vocabulary of symbolism evolves.

“I want to give these objects, which are regarded as valueless, a new story and move their history forwards,” he has said. “A broken object can still be as beautiful as a perfect object,” he adds, citing the Venus de Milo, armless but still venerated.

A game of opposites that chase each other, as in the new Milanese exhibition by the artist titled "Sometimes I look east, sometimes I look west". Quiet, thoughtful but at the same time witty and subversive, de Vries’s sculptures offer a second narrative opportunity to exquisite objects, such as a Cocoon Jar from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), which changed its essence in a few moments from fetish to potsherd. De Vries skillfully deconstructs these ancient fragments, giving them a new symbolism. The swarm of butterflies surrounding the pot in "Resurrection Jar" alludes on the one hand to the cocoon shape of the vase, and on the other to their iconographic use as a symbol of the resurrection in the famous still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age.

China and Holland are the extreme poles of his narration. The first seen as the driving force of ceramics manufacture throughout history, the second, as well as his home country, a nation that reaches world power in 17th century, via their trade with the east. Ceramics played a pivotal role in this, not only porcelain from China but also Dutch Delftware, much of it inspired by Chinese porcelain. However, de Vries's interest is not limited to a reflection on the genesis of ceramic products, their forms, their uses and symbols. His intellectual curiosity embraces historical and sociological insights into the context in which – yesterday as today – these are realized or exchanged.

Following this perspective, the rebirth of China as a global superpower becomes one of the most fascinating and urgent themes. De Vries reminds us of Napoleon Bonaparte's warning: “China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep, for when she wakes she will move the world.” The artist's work constantly reiterates the lesson of the Dutch masters de Heem, Kalf, van Alst and van Huysum, in whose paintings common pottery – milk jug, teapot or cress drainer – is imbued with references to vanitas and memento mori. Fruits, flowers and the small insects that accompany them were, in fact, indicators of veiled ethical and spiritual references.

In his oeuvre aesthetic conundrums find unexpected possible interpretations. In "Two Tang Soldiers" one of the pair of Tang dynasty (618-907) terracotta soldiers presents the typical earthy color and appearance of an archaeological find, while the other is painted by the artist with bright primary colors. Although the modern viewer is used to look at ancient objects – like, most famously, Greek marbles – in all their monochrome beauty, pure and white, in fact these pieces were originally painted, often in colours now considered garish. The same is true with the muddy nuances of these terracotta artifacts from China. Pairing these two soldiers reflects on today's aesthetic perception of these works in relation to the moment of their creation. De Vries does not take a position, but contrasts how the history of taste proceeds in an uninterrupted dialogue with the history of art; an apparently kitsch aesthetic can reveal a profound hidden truth.

Artworks by de Vries may be exploded, combusted, destructured or, on the contrary, recomposed using the kintsugi technique – the Japanese practice of using gold to reconnect the fragments of ceramic objects – the quality of execution is what distinguishes each of these technics. "There was a time,” says de Vries, “when quality was not considered an integral part of a contemporary work of art: the idea was the essential parameter for its success. But now I think there is a return to a vision of the artist as a producer, as someone who possesses a particular creative ability that allows him to give life to sublime works.” This does not mean rejecting the lessons of the contemporary that in his work is exalted through countless Dadaist, Surrealist and Pop quotes. In an aesthetic remix in which inspirations drawn from the world of high culture clash with those of low culture, we move from the Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti ("Egypt" 2013) to The Simpsons ("Marge Simpson as Guan Yin Goddess of Compassion" 2014).

Each sculpture by de Vries, while maintaining a dialogue with all his other works, remains essentially a single piece. This is one reason why the artist does not make use of assistants but creates every single work by himself. His sculpture is much about composition, balance and aesthetic. A lot of it develops in fieri as he works on it. In this context the largest work on show, "The Wall 2," is especially relevant. An installation of white Delftware inspired by the French-born, Dutch architect Daniel Marot, whose elaborate interior designs helped define the decorative style of Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. Marot’s wall schemes of blue and white Chinese porcelain were a status symbol of the time. In 2012 de Vries was invited to create a monumental work inspired by Marot by the English museum, Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, who commissioned him to create a site-specific installation for the museum's grand staircase. The temporary installation "Bow Selector" comprised four consecutive panels presenting in a unique and innovative way the museum’s precious collection of almost three hundred pieces of Bow Porcelain (London, 1747 to 1764). By contrast, for "The Wall 2" de Vries deliberately chooses only fragments of Delftware, saved from centuries old rubbish tips and dredged from the bottom of canals. These objects were not celebratory but kept for everyday use: it’s the artist who now gives them a new cultural status.

In this and other works on show the archaeological remains are the starting point for a new narrative. Perhaps one day they too will disappear into the earth and perhaps will be found in an unimaginable future. What stories will they tell then?

Born in 1960 in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Bouke de Vries studied at the Design Academy Eindhoven, and Central St Martin’s, London. After working with John Galliano, Stephen Jones and Zandra Rhodes, he switched careers and studied ceramics conservation and restoration at West Dean College. Every day in his practice as a private conservator he was faced with issues and contradictions around perfection and worth.Using his skills as a restorer (c.f. Ron Mueck’s model-maker skills), his ‘exploded’ artworks reclaim broken pots after their accidental trauma. He has called it ‘the beauty of destruction’. The more contemplative works echo the 17th- and 18th-century still-life paintings of his Dutch heritage, especially the flower paintings of the Golden Age, a tradition in which his hometown of Utretch was steeped (de Heem, van Alst, van Huysum inter alia), with their implied decay. By incorporating contemporary items a new vocabulary of symbolism evolves.